Conflict mineral are in most our electronic devices – no matter if smartphone, laptop, wireless headphones. But what are conflict minerals? And can you avoid them? That is what this article is about.

© Amnesty International and Afrewatch1, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Overview

Introduction

What are conflict minerals?

Why are they in my smartphone?

Laws in the US and the EU

And how does fair mining look like?

Alternatives to burying your head in the sand

The End

Footnotes

Introduction – Fair or unfair?

–> back to the Overview

“The global economy has been built on the sacrifice of certain people and places. And one of these places, that’s one of the primary sacrifice zones for the global economy is the Eastern Congo” says Julie Klinger, Associate Professor, Boston University, about the issue of conflict minerals.2

It is an inconvenient truth. But if we are honest, it’s nothing new for many people.

When I go into a supermarket, a clothing store, an electronics store in our globalized world and think about which tomato puree, which shirt, which phone I want to buy, there is not a lot of information about the journey the product took. Did the tomatoes grow on italian or chinese soil? How are the working conditions on the cotton plantation? And who did work on my phone? Do they have the opportunity to provide for themselves and their families with this job? Can they organize in unions?

Answers are rare.

For a lot of products there are labels that give answers, that give certainty about the production conditions. The FairTrade label, that certifies many product categories from bananas to cotton to rice. The utz-label that covers coffee, tea, cocoa. The GOTS-label for clothing.

But for electronics – laptops, phones, tablets, navigations systems, TVs, etc. – there are way less answers. Too many parts that altogether have about travelled around the world until the phone arrives in the store or gets send to me via mail order.

And for me the question arises – what will I do when my smartphone goes to the happy hunting-grounds? The questions arising from that – the recycling of electronics – have to be postponed for another time. Today is about the journey into life and what role conflict minerals play in that. The focus in this article lies on the direkt impacts on humans. It does not cover the impacts on the environment. Another important topic for another time is the sustainablity of rare earth minerals – neodymium for magnets, europium for display-colors, cerium to polish displays and others. These are also essential for our smartphone. But, let us get back to today’s business:

What are Conflict Minerals?

–> back to the Overview

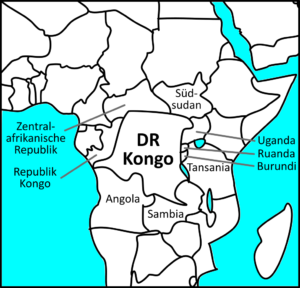

Whether a conflict mineral is a conflict mineral is decided by the person using the word. Let us here make use of the guideline which the OECD has published about that issue.3 According to that you call minerals conflict minerals, if their regions of origin are characterized by armed conflicts, widespread violence, political instability, and broken down infrastructure. In different terms: areas, where the government and the police/military don’t have a lot to say or they themselves are causing trouble. That applies to many areas in the world. But no conflict has coined the term “conflict minerals” as much as the East-Congo conflict in the DRC (Democratic Republic of the Congo).

The Democratic Republic of the Congo.4 A country as big as Western Europe. A country which did not have to exist – the borders so unfavourably drawn, that you have to use a plane to travel from the western capital, Kinshase, into the also densely populated East, the Great Lakes Region. After the Belgian colonial era, where Belgium and Europe enriched themselves with natural rubber, palm oil and ivory5 – came the dictatorship under Mobutu Sese Seko.6 The following 32 years dictatorship started with a military coup 1965, which had supporters from the other side of the Atlantic. The US, or rather the CIA “arranged, supported, and indeed managed Mobutu’s Coup.”7 And the assasination of the previous prime minister Patrice Lumumba8, the first head of government in the independent Congo, was planned partially by the CIA.9

The Democratic Republic of the Congo.4 A country as big as Western Europe. A country which did not have to exist – the borders so unfavourably drawn, that you have to use a plane to travel from the western capital, Kinshase, into the also densely populated East, the Great Lakes Region. After the Belgian colonial era, where Belgium and Europe enriched themselves with natural rubber, palm oil and ivory5 – came the dictatorship under Mobutu Sese Seko.6 The following 32 years dictatorship started with a military coup 1965, which had supporters from the other side of the Atlantic. The US, or rather the CIA “arranged, supported, and indeed managed Mobutu’s Coup.”7 And the assasination of the previous prime minister Patrice Lumumba8, the first head of government in the independent Congo, was planned partially by the CIA.9

The already by Belgium run-down and ruined state couldn’t recover during Mobutu’s cleptocracy. Later the consequences of the cruel genocide in the early 1990s in the neighbouring country Rwanda put an additional strain on the situation in the DRC. During that genocide almost 1 million people of the Tutsi ethnicity were killed. And let us note that the distinction Tutsi and Hutu was created by Belgian colonial rulers.10 After the Rwandan Hutu government is overthrown, more than 1 million Rwandans flee to the DR Congo – a lot of them Hutu-perpetrators in the genocide. They live in huge UN-refugee camps in the east. That fuels local conflicts between different ethnicities, religions and different nationalities – the East Congo cannot break away from the influence Rwanda and Burundi. After 32 year of dictatorship, the regime finally gets overthrown from a rebell coalition in the 1st Congo War 1996/1997. But this doesn’t mean peace – 2 wars follow. The first free elections finally take place in 2006 after 4 decades.

The East of the Congo remains in conflict – there are a lot of militias, armed groups, rebell groups. Kinshasa, the capital of the Congo, has only limited influence in the East Congo – too far the distance that can only be travelled by plane. Poverty, a high unemployment and lack of opportunities lead to young people joining armed groups.

These groups finance themselves through fees or “taxes” which the general public has to pay. No matter which business – from retailers, miners to bar and brothel owners. This fact shows how although conflict minerals can be seen as a cause of armed conflict – the attract criminality through their high value, like everything expensive in this world – they are even more a symptom. A possibility to make money, which, if the circumstances would grow too difficult, could also be earned with the exploitation of timber, for example. Congolese soldiers are also involved in these financial transactions. Sexual violence and violent deaths are common – The group ADF (Allied Democratic Forces) is being accused to have killed about 500 people from the middle of 2019 to the middle of 2020.11 The group NDC-R (a spin-off from the Nduma Defense of Congo) killed more than 130 civilians between 2018 and 2020. The Congolese Army cooperates with the armed groups.12 Since 2017 the Kivu Security Tracker13 collects more data on the crimes of armed groups. In the last 4 years there has unfortunately been a slight upward trend in the number of violent deaths.

And since armed groups do also finance themselves with the mining, trade or export of minerals, we call these minerals conflict minerals. The DR Congo is insanely rich in resources – copper and cobalt in the south, tin, tantalum and gold in the east, diamonds in the south-west – and that is an incomplete list. Often conflict minerals are called 3TG – tin, tantalum, tungsten, and gold – because among others, these are mined in the conflict rich regions.

The wealth in ressources is a curse and blessing. It fuels conflicts – valuable minerals are easy to trade and smuggle – and the mining can easily be controlled. On the other side it enables many people to provide for themselves and their families. Still the country is one of the poorest countries in the world.14

Why does the wealth in resources not lead to wealth of the Congolese people?15 Let us take a look how the largest global company in the area commodity trading, Glencore16 got the contracts to mine resources in the DRC. Dan Gertler, a business man known in the diamond industry, became the middle man in the negotiations between Congo’s president Kabila and Glencore in the early 2000s. Glencore got the mining licences for a knockdown price – for copper, they paid 20 % of the price agreed upon between the investors – and bribes amounting to more than 100 million US$ in between 2005 and 2015 – the value of the mining licences is in the ballpark of billions of US$.17

Why do I need them for my Smartphone?

–> back to the Overview

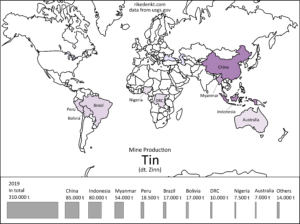

Almost 50 % of Zinn is used for soldering.18 Soldering is also what it is used for in smartphones. The circuit board, which is essential the brain of your smartphone, only works through the soldered tin. The DRC is an important producer of tin, even if globally, other countries produce way more.19

Tantalum is in practically all digital electronic devices in their condensators.20 Condensators can store energy or get rid of unwanted electrical impulses. Often people do not talk about Tantalum, but Coltan. Coltan is the ore from which Tantalum is concentrated.21

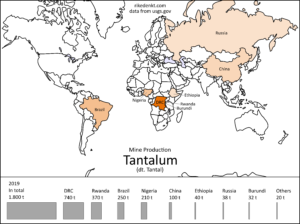

You can see below which countries produced the most Tantalum in 2019 – the DRC is one of the biggest producers.22

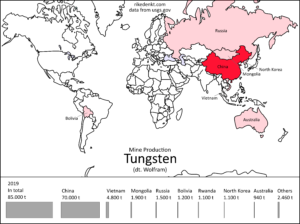

Tungsten is the element most stable to heat – that is why it is the little wire in our light bulbs. In smartphones it is included because of its high density in the little vibration motor as an imbalance.23 Although for the DR Congo the mineral is an important export commodity, globally the country is a small producer – for example, in 2017 the DRC produced 120 tons compared to 82.100 tons globally.24 So these are the main producers of tungsten:25

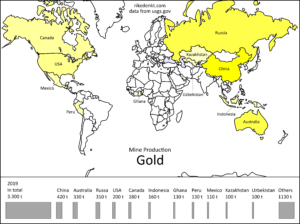

Only about a tenth of the global gold demand is in the technology sector. Much more prominent ist the jewellery sector and the demand for gold as a value-only material.26 In technological applications gold shines with his excellent conductivity, its good processability, lack of corrosion (rusting) or tarnish like silver. You need about 30 mg of gold (that is 0.03 grams) for a smartphone, mainly for the circuit board.27 The DR Congo produzed only about 1 % of the global production in 2017.28 Here are the biggest gold producers:29

The last mineral I want to present, is cobalt. Cobalt is not a conflict mineral, because their deposits are not in the conflict-rich East Congo, but in Congo’s south.30 But there are still problems – problems, that are common for mining in weakly governed areas:31

- Widespread child labour; other than the hard and dangerous work in shifts up to 12 hours long, that children in part start before age 10, they also often experience violence and abuse.

- High accident rate through mines collapsing, often resulting in deaths.

- Lung diseases because of working with metal dusts.32

- illegal “taxation” – meaning mine workers have to hand over part part of their earnings, often to government employees.

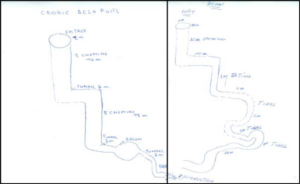

Here are 2 maps by mine workers showing the mine design:

© Amnesty International and Afrewatch33, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

© Amnesty International and Afrewatch33, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

These mines are built by the workers with simplest tools. Just looking at them, I honestly get a queasy feeling.

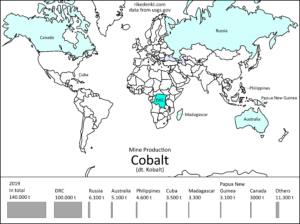

Cobalt is a “green” resource, saying – right now it is essential for switching to renewable energies. It is used in lithium-ion batteries that right now are the battery standard.34 Whether electric car, smartphone or big battery farms to store renewably produced energy – you need cobalt.35 And the DR Congo is the biggest producer of cobalt:36

What is Dodd-Frank and do the EU also have laws to conflict minerals?

–> back to the overview

To try to solve the issue of conflict minerals, section 1502 was added to the Dodd Frank Wall Act. Dodd Frank, in force since 2010, is actually a reform of the US financial markets law. But Section 1502 obliges all companies that are noted at the US-stock-exchange, to report on the use of the 3TG from the DRC and neighbouring countries. Additionally independent checks have to be done on the use of conflict minerals.

That sounds alright. But Dodd-Frank is being criticized for being designed from the outside (specifically in the US), without sufficient cooperation with the local actors like the government and civil societies.37

And it is disputed if and how the situation in the East Congo has improved through section 1502. Dodd-Frank has led to a huge drop in demand. Instead of satisfying the requests, companies chose suppliers who do not get their minerals from the DRC or neighbouring countries. The demand in Kivu for tin, tantalum and tungsten dropped by 75 – 90%, making about 400.000 artisanal miners unemployed.38

Let us quickly define artisanal mining. Artisanal mining is mainly poverty driven, miners work semi-independently and predominantly manual. About 15 – 20% of the world’s primary mineral output are mined this way – employing directly around 40 million people and supporting further 150 – 170 million people.39 For this quite informal mining sector, it is almost impossible to realize standards like Dodd-Frank. Additionally to artisanal mining, we distinguish between small-scale mining and large-scale mining.

Dodd-Frank also led to a big increase in smuggling. That leads to a financial gain of some of exactly the same people which financing should have been cut by this law.40 Two reports on behalf of the German Federal Environment Agency have concluded that a clear assessment of the effects from section 1502 of the Dodd-Frank-Act is difficult. Short term, more negative than positive, long term unclear.41 It would also have been better to introduce the law little by little to diminish negative consequences.

In an open letter from 2014, a fundamental problem was posed: treating the symptom of conflict minerals does not do a lot if the underlying causes like land, identity, and political competition in a militarized society do not get treated.42

Either way, now the EU wants something like that as well. Since 2021 regulation 2017/821 is effective, obliging importers of 3TG into the EU to establish similar risk management, as well as have third-party check ups. This does not apply to further processing. If the minerals are traded not in concentrated form, but in form of a microchip or battery, the due diligence processes are voluntary.43 We will see if the regulation thus only poses a toothless tiger.

Apart from these legislations – is there “fair” mining?

How does fair mining look like?

–> back to the overview

These legislations, Dodd-Frank and the EU-regulation, are only the fundation. As mentioned, these can lead to positive changes like the armed groups leaving the mine or preventing child labor in its worst forms,44 or lead to negative changes as increased smuggling. People can also lose their livelihoods, because big companies to not want to deal with the issue and rather source their minerals from somewhere else.

What makes the difference are the initiatives that locally make the legislation and due diligence applicable. But, as you might have thought, the efficiency of these initiatives is diverse and controversial. Everyone can say, they checked a mine and never saw a weapon or working child. Since the certification process should ideally be low-cost, there is a danger of this process turning into a box-ticking-exercise at the desk. So how can that be avoided? Important are for example:

- the standard. It defines social, ecological, and economical goals. Often it refers to other standards and legislations – for example section 1502 of the Dodd-Frank-Act and the OECD-guideline about conflict mierals, ILO-conventions about work safety, child labor, the EITI-standard about transparent money flows. There is no need to reinvent the wheel.

- a traceability system. The closed sacks of minerals are often tagged in the mine, for example with a bar code.45

- independent audits (check-ups of the mines) through third-parties. To be completely independent, these audits should not be financed by the auditees – that creates dependence. Ideally there should also be a rotating system, leading to changing auditors for a mine.

- a grievance system about abuses in the mine and wrongdoings of the audits.

Important for the success of an initiative are also the stakeholders, meaning which people make decisions. Are civil society actors present, union, local NGOs, affected communities? Or do all deciding people belong to the industry? Another factor is the motivation for the initiative. Is it about fullfilling laws, demands from buyers (business2business demand) or is it the interest of the consumer?

With these thoughts in mind, I want to present 3 initiatives to you.

- the monopolist. iTSCi46 is an initiative led by 2 industry associations. The local tasks are done by workers of the NGO PACT.47 The initiative almost has a monopoly regarding traceability systems. That and other things have been critizised.48

- the paper tiger. The RMAP49 uses the approach to certify smelters or refiners instead of mines, because the number of those is lower. In my opinion this also partially defeats the point, because smelters are often located in other countries, thus making it more difficult to assess if a mine is controlled by armed groups, if there are problem with safety or child labor, etc. It is more about a quick declaration as “conflict-free”, less about actively supporting suppliers and producers to improve. Civil societies are not included in the stakeholders.50 The audit reports are not publicly available.

- the Underdog. The IRMA-initiative51 has a good foundation with unions, affected communities, NGOs and companies as stakeholders. There are different levels that can be met – this could solve the criticism, that the requirements to mines are unattainable. Only a handfull of mines have been certified, but the initiative looks promising to me. The reports are publicly available.52 In contrast to iTSCi and RMAP, this initiative includes environmental issues: water, air, and soil pollution; mercury and cyanide.53

There are also other standards54 – but these 3 are the most important ones in my opinion. A 2018 report by Germanwatch grades these 3 and other initiatives according to different criteria like audit independence, grievance mechanism, public availability of reports, sanctions, etc. All 3 get the result partially credible.55 A lot of room for improvement. I see the most potential in IRMA because of included civil society stakeholders, broader coverage of topics and higher transparency.

Alternatives to burying your head in the sand

–> back to the overview

So you would now like to buy a smartphone, which uses minerals certified by the mentioned standards? Easier said than done. There is generally only information on how the producing company by and large deals with the issue, in conflict mineral or sustainability reports or at least on the company website. I looked at a few of the most sold smartphone-brands:

- Apple56 says that all their suppliers partake in a “Third-Party-Audit” program, RMAP or the certification by LBMA (London Bullion Market Association). The former we already know. LBMA is an international trading organization that does a similar certification, certifying refinieries. A report commissioned by the German Federal Institution for Geosciences and Natural Resources (BGR) does not find significant weaknesses, but there have been found serious Human Rights abuses in LBMA-certified gold-raffineries in Tanzania and Sudan.57

- According to Samsung58 all their suppliers are RMAP-certified.

- Xiaomi59 expresses it in an ambigious way – they require suppliers to follow RMAP-audit guidelines – which does not give information on the certification.

- Huawei60 does not give information on certification of suppliers.

- Nokia61 only looks at the 274 suppliers the spend 98% on, not regarding the 990 suppliers they spend 2% on. In a way understandable, because due diligence is rather costly for small suppliers, but the representation also seems quite manipulating. The 274 suppliers looked at lead to about 300 smelters, from which about 79% are RMAP or LBMA certified. 18% of the smelters were not certified or pursuing a certification, thus Nokia has requested them to be removed from its supply chain. Apart from that sounding weirdly passive, it sounds rather ambitious to me to replace such an amount of suppliers.

The reports read quite diverse – the one from Apple read the most like a company seeing a responsibility they have to live up to. Nokia’s report reads more like an expectation towards the suppliers, to solve the issue. This cannot work – the companies upstream, closer to the consumer, have the money, the attention, and the resources, to integrate due diligence processes, the companies downstream, closer to the mineral, have less money, attention, and resources.

Back to me personally – I wanted information specifically about the product that I buy, not about the entire company. There is only one smartphone at the moment, which provide that:

The Fairphone. My old smartphone died during the creation process of this blog entry an undignified death in a bucket of cleaning water. I decided after a while to buy the Fairphone 3. Starting as a Dutch campain for awareness, now they switched to producing a smartphone. Right now tin, tantalum, tungsten and gold – the 3TG – are mined under reasonably fair conditions, working with local initiatives and global organisations. The tin and tantalum are iTSCi certified in cooperation with the Conflict-Free Tin Initiative and Solutions for Hope.62 The tungsten is iTSCi and RMAP certified and is produced by the New Bugarama Mining Company in Rwanda.63 The gold is Fairtrade certified.64 They have many articles on their blog to different aspects. The most important difference for me was a different attitude. It is clearly about an improvement of the status quo, not just the declaration to be conflict-free.

If you are not convinced by the Fairphone, a used/refurbished phone could be suitable for you.

Or you look for a smartphone that is easier to repair. If you are not good at tinkering with stuff or like me, sometimes just fail at it, you can have it serviced.

Or simply forego. If you want to function in this society, you cannot forego a smartphone, but you can other devices. Do I need a TV, a fitness-bracelet, a fridge that itself can go shopping? The trend for “smart” devices connected to the “Internet-of-things” also means – more ressources. Why not less for a change? It is freeing, cheaper, and there is less stuff to break.

Last but definitely not least: talk about it. The issue is complicated, and I agree it’s not the best conversation starter. But the companies are enabled to stay intransparent by us not thinking and talking about what is in our gadgets and what journey it took.

The End

–> back to the overview

I hope you liked this introduction into conflict minerals and smartphones. The issue is multifaceted – you get everything from chemistry to world politics. But the solution does not have to bury your head in the sand65 and ignore the issues. Let us rather try to make decisions in good knowledge and conscience.

Feel free to share this article or sources with people who might be interested.

I am happy to receive feedback, questions, and mistakes at rike@rikedenkt.com.

Footnotes

–> back to the Overview

- Picture left: This is what we die for: Human Rights abuses in the Democratic Republic of the Congo power the global trade in cobalt. Amnesty International and Afrewatch. 2016. Report. https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/afr62/3183/2016/en/. Last checked on 14.07.2021.

Picture right: Profits and loss: Mining and human rights in Katanga, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Amnesty International and Afrewatch. 2013. Report. https://www.amnesty.nl/actueel/profits-and-loss-mining-and-human-rights-in-katanga-democratic-republic-of-the-congo. Last checked on 14.07.2021. - Source: Conflict and Coltan in Eastern Congo Boston University. 2016. Video. youtu.be/F5VZtJDYWNM. Last checked on 14.07.2020.

- The OECD is the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 37 rich countries who try to figure out how the world should be run. The named guideline is the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas.

Source: OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas. OECD Publishing. 2016. Guideline. https://doi.org/10.1787/3d21faa0-de. https://www.oecd.org/publications/oecd-due-diligence-guidance-for-responsible-supply-chains-of-minerals-from-conflict-affected-and-high-risk-areas-9789264252479-en.htm. Last checked on 13.07.2021. - Not to be confused with the Republic of the Congo. Since its colonization there are 2 Congos. Both countries are named after the Congo-river running between them. During the Berlin Conference 1884 – 1885 the south-eastern area was given to the Belgians, while the French got the north-western part.

Source: Why There Are Two Congos in Africa. Nii Ntreh, Face 2 Face Africa. 2020. Article. face2faceafrica.com/article/why-there-are-two-congos-in-africa. Last checked on 13.07.2021. - In a time, where fittingly wheels were just becoming a bulk commodity.

- President Mobutu tried to ban everything European to have a more authentic Congo (for this exact reason the name of the Congo was changed to Zaire). Part of that change was the ban of European names. He himself, Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, changed to Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga. One of the two existing translations is „Mobutu Sese Seko, the cock who even in the hindmost backyard leave no chick unbred.“

Source: Kongo: Kriege, Korruption und die Kunst des Überlebens. 2014. Dominic Johnson. Buch. Frankfurt am Main: Brandes & Apsel. ISBN 978-3860997437. - Source: An Extraordinary Rendition, Intelligence and National Security. Stephen R. Weissman. 2010. Journal Artikel. Volume 25, Issue 2. DOI: 10.1080/02684527.2010.489277.

- Yes, the alcoholic drink is named after Patrice Lumumba.

- Source: Why did the US support Joseph Mobutu. Joseph Hesketh, Observing Africa. 2016. Article. https://observingafrica.wordpress.com/2016/02/18/why-did-the-us-support-joseph-mobutu/. Last checked on 13.07.2021.

- The Belgians reduced complex pre-colonial power relations to one “race”, which was even registered in the passport. Tutsis where people who had a lot of cows.

Source: Kongo: Kriege, Korruption und die Kunst des Überlebens. 2014. Dominic Johnson. Buch. Frankfurt am Main: Brandes & Apsel. ISBN 978-3860997437 - Source: Gunmen kill more than dozen civilians in eastern DR Congo attacks. Al Jazeera. 22.6.2020. News Article. aljazeera.com/news/2020/06/gunmen-kill-dozen-civilians-eastern-dr-congo-attacks-200622054441574.html. Last checked on 13.07.2021.

- Source: DR Congo: Wanted Warlord Preys on Civilians. Human Rights Watch, 2020. Article. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/10/20/dr-congo-wanted-warlord-preys-civilians. Last checked on 28.06.2021.

- A joint project from the Congo Research Group and Human Rights Watch

- According to GDP, adjusted for purchase power and per capita, the DRC is the 6th poorest country, followed by Malawi, Central African Republic, Somalia, South Sudan and Burundi.

Source: World Economic Outlook database: April 2021. International Monetary Fund. 2021. Data set, values for 2019. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2021/April/download-entire-database. Last checked on 14.07.2021. - For anyone interested in the question “Why does a general public seldomly profit from a country’s resources?”, I can recommed The Dictator’s Handbook by Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and Alastair Smith.

- Sectors metal, minerals, fossil fuels; headquarters in Switzerland; 135 000 employees worldwide.

Glencore will probably be the company providing cobalt for Tesla’s new giga factory in Berlin. Source: Tesla secures new cobalt deal as it phases out the controversial mineral. Fred Lambert, Electrek. 16.06.2020. Article. https://electrek.co/2020/06/16/tesla-secures-cobalt-deal-controversial-material/. Last checked on 13.07.2021. - Source: The Broken Heart of Africa. Süddeutsche Zeitung. 5.11.2017. News Article. https://projekte.sueddeutsche.de/paradisepapers/wirtschaft/mining-for-control-in-glencore-s-congo-e774511/. Last checked on 13.7.2021.

- Source: Zinn. Informationen zur Nachhaltigkeit. Bundesanstalt für Geowissenschaften und Rohstoffe, Jürgen Vasters, Gudrun Franken. 2020. Report. https://www.bgr.bund.de/DE/Themen/Min_rohstoffe/Produkte/Informationen_zur_Nachhaltigkeit/zinn_verzeichnis.html. Last checked on 13.07.2021.

- Source: Tin Statistics and Information: Annual Publications – 2019. US Geological Survey, National Minerals Information Center. 2020. Report. https://www.usgs.gov/centers/nmic/tin-statistics-and-information. Last checked on 13.07.2021

- Tantalum condensators are suitable for high frequencies – and digital circuits often produce unwanted high frequency electric noise.

Source: Die Elemente – Bausteine unserer Welt. Theodore Gray. 2013. Book. Komet Verlag Gmbh. ISBN 978-3869410036 - Coltan is an abbreviation for columbite-tantalites. It is a mineral ore containing tantalum as well as niob, which used to be called columbite.

Columbite is named after Christoph Kolumbus, who by the way also gave the name to Columbia, a poetic personification of the US: click me. Since the 1920s she has gone out of fashion, but remember the torch-carrying woman at the beginning of Columbia Pictures movies? That is a Columbia.

Source: When America Was Female. The Atlantic, Garance Franke-Ruta. 5.3.2013. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2013/03/when-america-was-female/273672/. Last checked on 13.07.2021. - Source: Niobium (Columbium) and Tantalum Statistics and Information: Annual Publications – 2019. US Geological Survey, National Minerals Information Center. 2020. Report. https://www.usgs.gov/centers/nmic/niobium-columbium-and-tantalum-statistics-and-information. Last checked on 13.07.2021.

- The density of tungsten is almost the same as the density of gold, which makes it useful for gold counterfeits..

Source: Die Elemente – Bausteine unserer Welt. Theodore Gray. 2013. Book. Komet Verlag Gmbh. ISBN 978-3869410036 - Source: 2017 Minerals Yearbook – Tungsten [Advance Release]. US Geological Survey, National Minerals Information Center. 2020. Report. https://www.usgs.gov/centers/nmic/tungsten-statistics-and-information. Last checked on 13.07.2021

- Source: Tungsten Statistics and Information: Annual Publications – 2019. US Geological Survey, National Minerals Information Center. 2020. Report. https://www.usgs.gov/centers/nmic/tungsten-statistics-and-information. Last checked on 13.07.2021.

- Source: Gold Demand Trends Full year and Q4 2020. World Gold Council. 28.01.2021. Website. https://www.gold.org/goldhub/research/gold-demand-trends/gold-demand-trends-full-year-2020. Last checked on 13.07.2021.

- Source: A golden opportunity: The risks and rewards of gold recycling. Tirza Voss, Fairphone Blog. 25.9.2020. Artikel. http://fairphone.com/en/2020/09/25/a-golden-opportunity-the-risks-and-rewards-of-gold-recycling/. Last checked on 14.07.2021.

- Source: 2017 Minerals Yearbook – Gold [Advance Release]. US Geological Survey, National Minerals Information Center. 2020. Report. https://www.usgs.gov/centers/nmic/gold-statistics-and-information. Last checked on 13.07.2021.

- Source: Cobalt Statistics and Information: Annual Publications – 2019. US Geological Survey, National Minerals Information Center. 2020. Report. https://www.usgs.gov/centers/nmic/cobalt-statistics-and-information. Last checked on 18.07.2021.

- At the border to Zambia, where the DRC’s copper deposits are as well.

- Source: This is what we die for. Human Rights Abuses in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Power the Global Trade in Cobalt. Amnesty International and African Resources Watch. 2016. Report. https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/afr62/3183/2016/en/. Last checked on 13.07.2021.

- Not only “developmenting countries” have this problem. About lung diseases in the US I can recommend this podcast episode: Black Lung Disease from Sawbones (https://open.spotify.com/episode/360hPBsFo0jjdjYQV2EFUN?si=wfBCQcemQRiDC09sfKFX8Q&dl_branch=1)

- Source pictures: This is what we die for: Human Rights abuses in the Democratic Republic of the Congo power the global trade in cobalt. Amnesty International and Afrewatch. 2016. Report. https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/afr62/3183/2016/en/. Last checked on 14.07.2021.

- Are there any alternatives on the horizon? There are quite a few. Lithium-solid-state batteries and lithium-sulfur-batteries would have higher energy densities – meaning less weight per storage capacity, and thus less needed lithium. However, in the case of lithium-solid-state batteries they are not safe enough yet, and in the case of the lithium-sulfur-battery do not endure enough charging cycles yet. According to Holger Althues, head of department in the field battery technology at the Fraunhofer Institute Dresden, both battery types need about 10 years until they can compete against the lithium-ion-battery.1 Right now the sodium-ion-battery could win the race – but the batteries would be heavier.2 That makes them more suitable for uses where weight is not a priority, e.g. electric cars. There are 2 resons for the higher weight: a 0.3 Volt lower cell voltage than for lithium-ion-batteries, and sodium being three times as heavy as lithium. That leads to 6.5 kg per kWh energy capacity instead of the 4 kg lithium-ion-batteries can reach. But, they would already be cheaper in mass production. Factories now producing lithium batteries, could even be converted for sodium-ion batteries. And the biggest benefit – no need for lithium or cobalt. 2 of the biggest battery producers, Faradion and CATL, are starting commercial production of sodium-ion-batteries.3 But let us stay in the present.

Source 1: Die Suche nach Alternativen zum Lithium-Ionen-Akku. Batterieforschung. Deutschlandfunk, Maximilian Schoenherr. 25.03.2020. Article. https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/batterieforschung-die-suche-nach-alternativen-zum-lithium.676.de.html?dram:article_id=473263. Last checked on 13.07.2021.

Source 2: Ausnahmsweise ein echter Durchbruch in der Akkutechnik. Natrium-Ionen-Akkus. golem.de, Frank Wunderlich-Pfeiffer. 17.06.2020. Article. https://www.golem.de/news/natrium-ionen-akkus-ausnahmsweise-ein-echter-durchbruch-in-der-akkutechnik-2006-149130.html. Last checked on 13.07.2021.

Source 3. Natrium-Ionen-Akkus werden echte Lithium-Alternative. golem.de, Frank Wunderlich-Pfeiffer. 18.6.2021. Article. https://www.golem.de/news/akkutechnik-und-e-mobilitaet-natrium-ionen-akkus-werden-echte-lithium-alternative-2106-156863.html. Last checked on 14.07.2021. - Cobalt is not only indispensable for batteries, but also for us humans. The molecules of the vitamin-B12-group have 1 cobalt-atom at their center. Vitamin B12 cannot be produced by humans and animals – only by micro organisms like bacteria. They live in the digestive tracts of humans and animals and produce vitamin B12. Cows as ruminants can take advantage of that ideally, bunnies need eat their droppings, and we humans prefer to supplement the vitamin – especially as a vegetarian or vegan.

- Source: Cobalt Statistics and Information: Annual Publications – 2019. US Geological Survey, National Minerals Information Center. 2020. Report. https://www.usgs.gov/centers/nmic/cobalt-statistics-and-information. Last checked on 18.07.2021.

- “It is possible to have some type of system, but it needs to be designed in cooperation with local actor, with national actors, not engineered from outside like Dodd-Frank has been.”

Source 1: Conflicted: The Fight over Congo’s Minerals – Fault Lines. Al Jazeera English. 18.11.2015. Video. https://youtu.be/27BZgQ5ln0w. Last checked on 13.7.2021.

Source 2: ‘Conflict Minerals’ – An Open Letter. 2014. Aloys Tegera, Eric Kajemba, et al. 9.9.2014. Offener Brief. https://suluhu.org/2014/09/09/conflict-minerals-an-open-letter/. Last checked on 30.06.2021. - Source: Does Your Smartphone Fund Conflict in the DRC? – The Stream. Al Jazeera English. 3.1.2012. Video. youtu.be/nNal_K-o6xw. Last checked on 13.7.2021.

- Source: Successful implementation of conflict mineral certification and due diligence schemes and the European Union’s role: lessons learned for responsible mineral study. Strategic Dialogue on Sustainable Raw Materials for Europe (STRADE). 2018. Report. https://www.stradeproject.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/pdf/STRADE_Report_D4.19_Due_Diligence_Certification.pdf. Last checked on 14.07.2021.

- Source 1: Conflicted: The Fight over Congo’s Minerals – Fault Lines. Al Jazeera English. 18.11.2015. Video. https://youtu.be/27BZgQ5ln0w. Last checked on 13.7.2021.

Source 2: How Congress Devastated Congo. The New York Times, David Aronson. 7.8.2011. News article. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/08/08/opinion/how-congress-devastated-congo.html. Last checked on 13.7.2021.

Source 3: Conflict Minerals in the Congo: Let’s Be Frank About Dodd-Frank. Mvemba Dizolele. HuffPost. 22.10.2011, huffingtonpost.com/mvemba-dizolele/conflict-minerals-congo-dodd-frank_b_933078. - Source 1: Auswirkungen des Dodd-Frank Act Sektion 1502 auf die Region der Großen Seen. Lukas Rüttinger et al., adelphi. 2016. Report. umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/1968/dokumente/2017-01-12_rohpolress_ka7_wirkung_dfa_1502_in_der_drc_pb2.pdf. Last checked on 14.07.2021.

Source 2: UmSoRess Steckbrief Dodd-Frank Act. Lukas Rüttinger, adelphi. 2015. Report. umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/378/dokumente/umsoress_kurzsteckbrief_dfa_final.pdf. Last checked on 14.07.2021. - Source: ‘Conflict Minerals’ – An Open Letter. 2014. Aloys Tegera, Eric Kajemba, et al. 9.9.2014. Open Letter. https://suluhu.org/2014/09/09/conflict-minerals-an-open-letter/. Last checked on 30.06.2021.

- Source: Merkblatt: Die EU-Konfliktmineralien-Verordnung. DIHK, BDI. 10.6.2020, ihk-muenchen.de/ihk/Umwelt/Konfliktmineralien_Merkblatt_2020.pdf. Last checked on 18.07.2021.

- This phrase includes for example slavery, forced labor, prostitution, or work harmful to a childs’ health and safety.

Source: C182 – Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention. International Labour Organization. 1999. Convention. https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C182. Last checked on 18.07.2021. - To complement this system, the German Federal Institution for Geosciences and Natural Resources (BGR) has developed an analytical fingerprint. Minerals can reveal a lot about their origin through their composition – using a data bank and statistics, one can make a statement on if the declared origin is plausible.

Source: Introduction to the Analytical Fingerprint. Bundesanstalt für Geowissenschaften und Rohstoffe. Website. https://www.bgr.bund.de/EN/Themen/Min_rohstoffe/CTC/Analytical-Fingerprint/analytical_fingerprint_node_en.html. Last checked on 12.07.2021. - iTRi Tin Supply Chain Initiative from the International Tin Research Institute (iTRi)

- Standing for: Private Agencies Cooperating Together. Founded in 1971.

- – that the initiative is too dependent on government agencies – in a country with a weak government, this can pose problems;

– that the initiative is too heavily influenced by companies – leading to lower prices for the mining workers;

– that fraud (minerals being declared as conflict-free despite being not) is not efficiently combated;

– that the tagging process takes place at special iTSCi-stations, instead of at the mines – making fraud easier;

– there’s more, but let’s leave it at that.

I found as much criticism about iTSCi because of the initiative being as prevalent, in comparison the IRMA-initiative does not have as much information due to the newness and low prevalence.

Source: ITRI Tin Supply Chain Initiative (iTSCi). UmSoRess Steckbrief. adelphi, Lukas Rüttinger, Laura Griestop, Johanna Heidegger. 2015. Report. https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/378/dokumente/umsoress_kurzsteckbrief_itsci_final.pdf. Last checked on 18.07.2021. - Responsible Minerals Assurance Process of the Responsible Minerals Initiative. The Standard used to be called Conflict Free Smelter Program.

- Source: Conflict-Free Smelter Program (CFSP). UmSoRess Steckbrief. adelphi, Lukas Rüttinger, Laura Griestop. 2015. Report. https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/dokument/umsoress-steckbrief-oecd-conflict-free-smelter. Last checked on 15.07.2021.

- Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance. Founded in 2006.

- https://map.responsiblemining.net/

- Source: Governance of Mineral Supply Chains of Electronic Devices. Germanwatch, Johanna Sydow, Antonia Reichwein. 2018. http://www.germanwatch.org/en/15418. Last checked on 18.07.2021

- Including:

RCM (Regional Certification Mechanism): developed by the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR), whose members are 12 African countries in that area.

CTC (Certified Trading Chains): developed by the German Federal Institution for Geosciences and Natural Resources (BGR), now applied in the RCM.

Fairtrade Gold Standard. - Source: Governance of Mineral Supply Chains of Electronic Devices. Germanwatch, Johanna Sydow, Antonia Reichwein. 2018. Report. http://www.germanwatch.org/en/15418. Last checked on 18.07.2021.

- Source: Special Disclosure Report. Apple Inc. 2021. Report. https://www.apple.com/supplier-responsibility/pdf/Apple-Conflict-Minerals-Report.pdf. Last checked on 18.07.2021.</em>

- Source 1: UmSoRess Steckbrief LBMA Responsible Gold Guidance. Lukas Rüttinger, Christian Böckenholt, Laura Griestop, adelphi. 2015. Report. https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/378/dokumente/umsoress_steckbrief_lbma_rgg_final.pdf. Last checked on 18.07.2021.

Source 2: Does a New „Gold Standard“ Really Protect Miners?. 30.06.2021. Article. Juliane Kippenberg, Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/06/30/does-new-gold-standard-really-protect-miners. Last checked on 18.07.2021. - Source: Samsung Electronics’ Responsible Minerals Report. Samsung Electronics. 2020. Report. https://images.samsung.com/is/content/samsung/assets/global/our-values/resource/2021_Sustainability_Report.pdf. Last checked on 18.07.2021.

- Source: 2020 Sustainability Report. Xiaomi Corportation. 2021. Report. https://www.mi.com/global/about/sustainability/. Last checked on 18.07.2021.

- Source: Huawei Statement on Responsible Mineral Supply Chain Due Diligence Management. Huawei. Website. https://www.huawei.com/en/declarations/huawei-statement-on-responsible-mineral-supply-chain. Last checked on 18.07.2021.

- Source: Nokia Conflict Minerals Report for 2019. Nokia. 2020. Report. https://www.nokia.com/sites/default/files/2020-06/Nokia-Conflict_Minerals_Report_for%202019_fin1.pdf. Last checked on 18.07.2021.

- Source: Tin und Tantalum Road Trip. Fairphone Blog. 08.11.2012. Blog Article. https://www.fairphone.com/en/2013/11/08/tin-and-tantalum-road-trip/. Last checked on 19.07.2021.

- Source: Supporting conflict-free tungsten in Rwanda. Fairphone Blog. 13.01.2016. Blog Article. https://www.fairphone.com/en/2016/01/13/supporting-conflict-free-tungsten-in-rwanda/. Last checked on 19.07.2021.

- Source: How we got Fairtrade certified gold in the Fairphone 2 supply chain. Fairphone Blog. 27.01.2016. Blog Article. https://www.fairphone.com/en/2016/01/27/how-we-got-fairtrade-certified-gold-in-the-fairphone-2-supply-chain/. Last checked on 19.07.2021.

- Ostriches do not bury their heads in the sand in case of danger. That seems to have been made up by Arabic authors. However, they sometimey lay down flat on the ground, to be overseen from a distance.

Source: Kein Kopf im Sand. Christoph Drösser, Die Zeit. 27.05.1998. News article. Issue 22/1998. http://zeit.de/stimmts/1998/1998_22_stimmts. Last checked on 19.07.2021.